How is noise measured? and How loud is too loud?

In order to fully understand how noise pollution affects both our health and quality of life, we need to first understand how sound is measured. Sound is measured in decibels, and it can be tricky to determine what level of noise is too loud. In this article, we will take a look at the science behind measuring sound, but we will also look at some ordinary activities and create our own scale-of-thumb for noise measuring and understanding just what sound levels are acceptable and which ones aren’t.

What is a decibel and how do they work?

A decibel (dB) is a unit of measurement that represents how loud a sound is. The louder the sound, the higher the dB reading will be. In order to measure noise levels, we use a device called a Sound Level Meter (SLM). This machine gives us objective measurements of noise so that we can ensure that our environment is not too loud.

If you want to get into the science of what a decibel is,

a decibel (dB) is a unit for expressing the ratio between two physical quantities, usually amounts of acoustic or electric power, or for measuring the relative loudness of sounds. One decibel (0.1 bel) equals 10 times the common logarithm of the power ratio.

Encyclopedia Britannica

But don’t worry, for those of us who are not particularly good at math and formulas, a decibel is simply a degree of loudness.

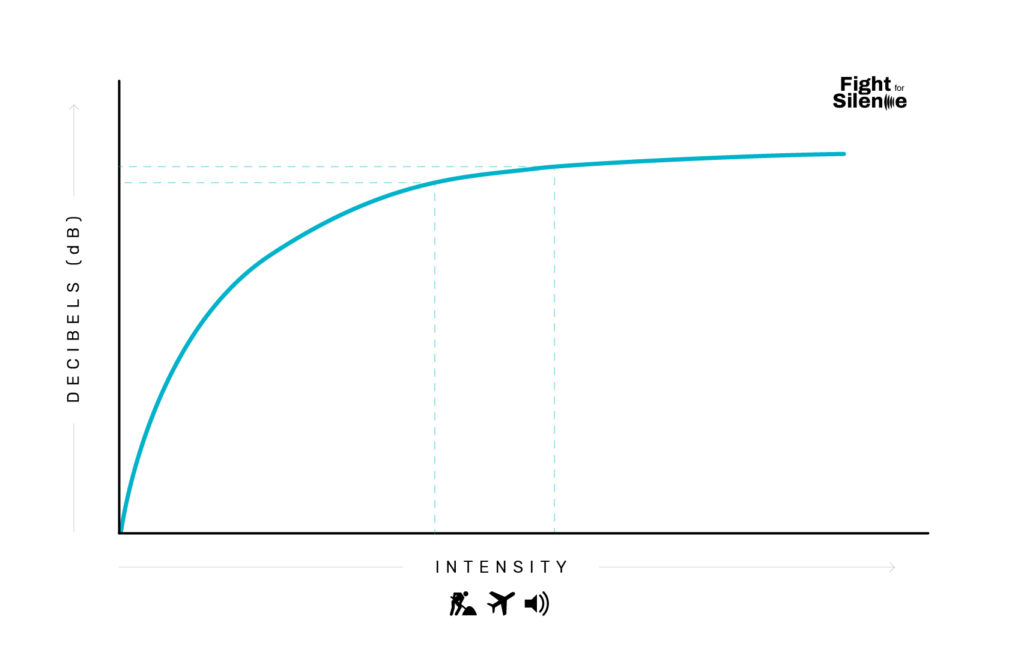

Now, even though we do not need to understand the formula, it’s important to understand how decibels work. This is often not as intuitive as one would hope, due to the logarithmic nature of the decibels scale. When we start measuring noise levels in real-world scenarios, the numbers might not seem to increase much, but that doesn’t mean the volume hasn’t changed much. 60 dB might look like only roughly 6% louder than 57 dB, when in reality 60 dB is perceived by us humans as twice as loud as 50 dB!

The decibel scale is logarithmic, which means that an increase of just three decibels actually represents a doubling of the noise. At least on paper that is true, in real life there are frequencies and other variables involved, so the rule of thumb is that a 6db increase equals doubling the perceived volume.

The good news is sound sources also add up logarithmically. This means that if a source of sound (let’s say a speaker) is generating 50 dB, and we add a second identical speaker, the result will not be 100 dB, it would actually just be 53 dB. It would take roughly 10 times the same source of sound generating 50 dB to generate a perceived volume of 100 dB. This is why it doesn’t really matter how many cars are passing through a highway, the sound level remails almost the same to us. 10 cars vs. 12 cars? We couldn’t possibly tell the difference in terms of volume.

A day-to-day sound measuring scale

Now that we understand how decibels work, let’s look at how different common activities measure up on the decibel scale.

- 30 dB: This is the sound of a quiet room.

- 60 dB: This is the sound of normal conversation.

- 70 dB: The sound of an average vacuum cleaner.

- 90 dB: This is the sound of lawnmowers and leaf blowers, or a kitchen blender.

- 100 dB: This is the sound of a car horn.

- 120 dB: This is the sound of an ambulance siren.

- 140 dB: This is the sound of a jet engine.

Unfortunately, there are other variables other than the decibels that come in to determine whether a sound might be harmful to your hearing. But it can be shocking to learn how many daily activities actually have the potential to cause permanent damage to our hearing. Any sound over 85 dB is potentially damaging, depending on how long you are exposed to it.

The following list can help you understand just how often you are exposed to sounds that might seem harmful, but they could be.

- Listening to music on your headphones: This is usually around 85-90 dB.

- Using a power drill: This is usually around 100 dB.

- Going to a rock concert: This is usually around 120 dB.

- Being in a thunderstorm: This is usually around 140 dB.

How loud is too loud?

Now that we’ve looked at how noise is measured and some real-world examples of how loud different activities are, let’s answer the question: how loud is too loud?

As we said, the answer to this question is not always clear, as it depends on a number of factors, including how long you are exposed to the noise and how close you are to the source of the noise.

In general, however, experts recommend keeping noise levels below 85 dB in order to avoid permanent damage to your hearing. This means that you should avoid activities that are much louder than this, such as going to rock concerts too often, attending motorsport events without proper hearing protection, etc.

If you are exposed to noise levels above 85 dB for extended periods of time, it’s important to take breaks and give your ears a rest. Wearing earplugs or noise-canceling headphones can also help increase how long you can be exposed to certain noisy activities without those noises being a threat to your hearing.

[…] that the relationship between sound intensity and perceived volume is logarithmic, which means that reducing the volume of sirens from 100-120 dB to 90 dB would actually be a huge […]

[…] home. Sometimes, the washing machine or the vacuum sound is enough to put your baby to sleep! Just make sure that the volume is low enough or the machine is far enough from the crib, so it doesn’t hurt your baby’s […]

[…] more limited options (nature only). Some apps also allow you to customize the sound, such as by adjusting the volume or setting a […]

[…] can produce up to 120 dB, with the average models being closer to the 100 dB mark. Remember that decibels are a logarithmic scale, which means that each increase of 10 dB represents a 2-fold increase in loudness. Therefore, the […]

[…] If you know how noise is measured, then these indications might be helpful. For residential environments, the accepted decibel level is lower than for street nuisance. Any noise exceeding 70 dB is considered disturbing. For instance, a stereo or boom box’s sound level is around 110 to 120 dB. […]

[…] horns go up to 110 decibels, which is very loud! On top of having these super powerful horns, trains are required by law to use them for 15 to 20 […]

[…] that all other factors are the same, a doubling in wattage usually means a 3db increase in the maximum volume of the speaker, which is equal to a doubling of perceived noise, meaning that a speaker with twice the wattage will sound about twice as loud at […]

[…] details to consider, but one that many people don’t seem to consider, and they should, is the level of noise you can expect to endure at […]

[…] perspective, consider this: standing next to a firing 9mm handgun (150-160 dB) is equivalent to standing within 100 feet of a roaring jet taking off, which is loud enough to cause immediate and permanent hearing […]

[…] next step is defining what is considered too loud, and this is where things start getting a bit tricky. The ordinance establishes the following […]

[…] describes altitude, the decibel scale describes something that is somewhat unexpected; pressure. The decibel scale is based on how much pressure is applied to the ear by a sound; the higher the pressure, the […]